The Bear has returned for the first time in a decade.

“Down, down, down, down

I’m goin down, down, down, down

I’m goin down, down, down, down

I’m goin down, down, down, down”

Bruce Springsteen may have been singing about a forlorn lover in his 1982 song, “I’m Going Down”, but it could have easily been about the stock market over the past couple of weeks.

By most metrics, we are now in a bear market (20%+ fall in prices) in both domestic and foreign stock markets. It is easy to look back and say that you saw it coming. You may be feeling regret about the losses we have incurred since the peaks back in January. And all of that is perfectly normal. As will be claims by some that they predicted this, and will be able to again.

These events tend to occur every three to four years, historically. If we’re honest with ourselves, we all have been worried about a selloff since the last bear market ended in March of 2009, while the S&P 500 was making gains of over 300% . You would have left a lot of meat on the bone had you been sitting in cash waiting since then. As a matter of fact, the leading theories regarding why stocks tend to outperform bonds or cash over time suggest it is exactly this type of market volatility that allows for the rewards of higher returns.

Will It Impact Your Plan?

I recently had a conversation with a client that wanted to move about 10% of her portfolio to cash. We spent some time discussing her goals and analyzing the impact of being more conservative. The models, which include expectations of volatility, suggested her likelihood of reaching her goals dropped below an acceptable range if she was too conservative. With that information, she decided to stick with her plan.

I always try to answer a question when discussing a change of investment strategy with a client, “Will it materially impact your ability to reach your goals?” That’s my job as an advisor, to help you make informed decisions. I don’t believe that I, or anyone else, can consistently predict what the market, or the Fed, or the President, or some other country’s leader will do tomorrow. I do know that occasionally the market goes down.

I also know that it eventually will recover, although the timing of that is uncertain. While that may not be comforting, it can be helpful to focus our attention on what we can control. I once made a client pretty upset trying to make a similar point, but perhaps there is a lesson there for all of us.

Control the Controllable

I used to manage a fairly large office of brokers at a very large brokerage firm. Each morning, I would receive a report of outgoing transfers to competitors. One of my responsibilities was to reach out to those clients that were transferring their account to understand what may have led to wanting to leave. Ultimately, though not always successful, I also hoped to convince them to change their mind.

The conversation normally started by asking questions to try and get a better understanding of why they wanted to move in the first place. If they were seeking lower costs, I could offer them discounted commissions or free trades. If they didn’t like their broker, I could introduce them to someone that may be a better fit. On occasion, however, a client would give me a reason that I found difficult to address.

One such reason was when the client had a relative that had become a broker or insurance agent. I just always assumed that if someone was moving an account due to family ties, there wasn’t anything I could offer that would change their minds.

Until, one day, I thought I found the perfect answer.

A client was transferring out a large retirement account that was worth a couple of million dollars. When I reached him on the phone, he politely explained that he had been very pleased with everything we had done for him over the years but that his son had taken a job at a broker and he felt compelled to help him out. When I asked what he was planning to invest in as an alternative to the relatively low-cost mutual funds he owned, he answered that, “it’s some sort of guaranteed annuity”.

“How much does it cost,” I asked?

“I’m not completely sure,” he replied.

I then asked if he would mind telling me the name of the annuity. He provided that and I proceeded to look up the details in a Morningstar® annuity analysis tool. It turned out, the product he was transferring to was a variable annuity that had a menu of mutual funds (known as sub-accounts) to choose from. The “guarantee” that he referred to would provide an income stream starting in about 10 years if he was willing to trade his ability to liquidate the annuity for the promise of an ongoing monthly check for the rest of his life.

It was going to cost him at least 1% more per year than he had been paying us for his mutual fund portfolio. Another catch was that he would be subject to surrender penalties if he wanted to withdraw his funds before the 10 years was up.

“But he is going to put me in funds that have done really well,” he said.

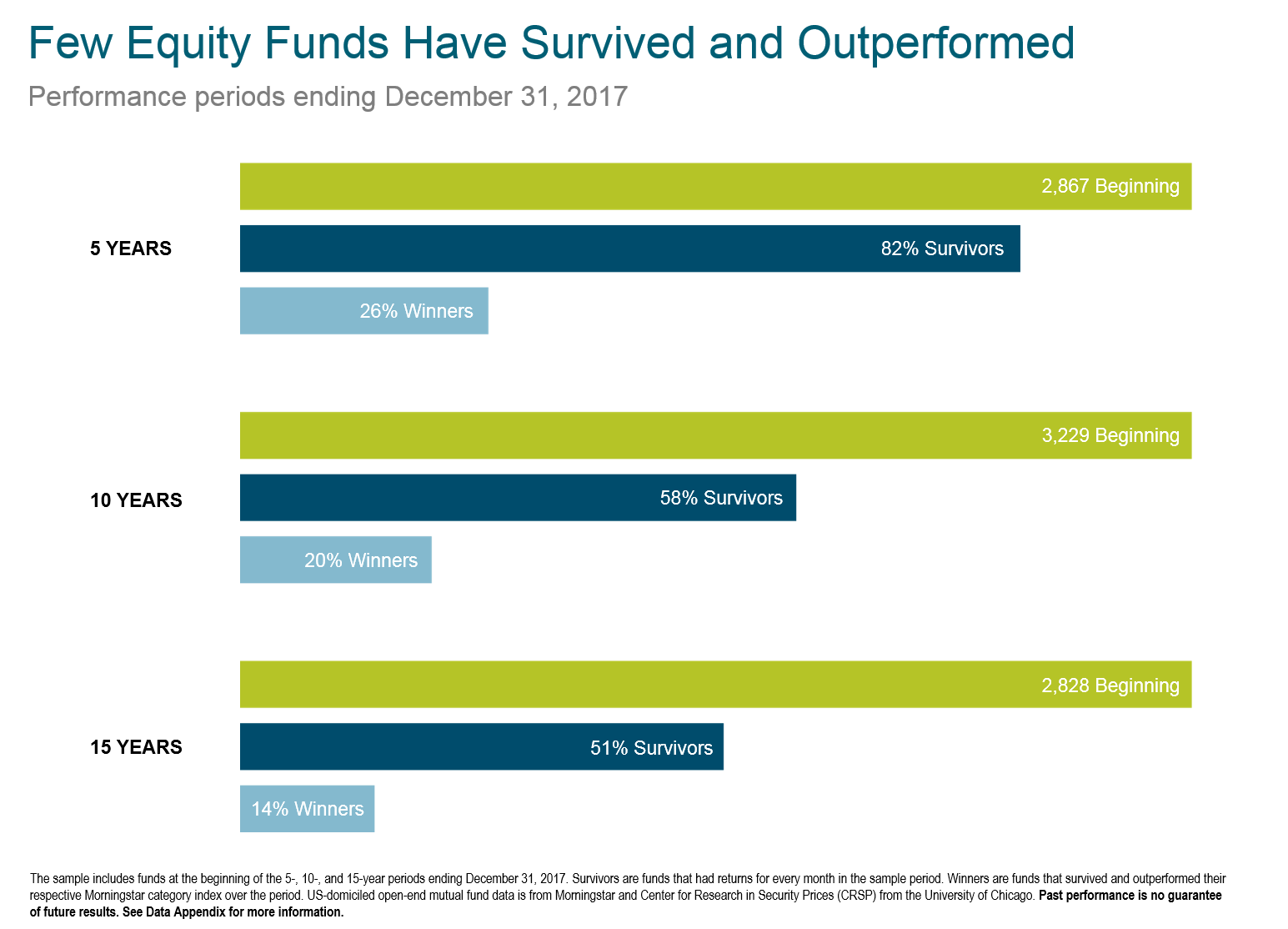

That led to a conversation about the differences between cherry picking funds that have done well in the past versus trying to select those that will do best in the future. We reviewed how few funds actually outperform over time, such as seen in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1. The number of mutual funds that survive and beat their benchmarks are significantly less than random chance would suggest.

We went on to talk about how one particular attribute of a mutual fund over any other seems to correlate with good performance, and that is cost, as seen in Exhibit 2.

Exhibit 2. Costs seem to be highly correlated to investment performance, or lack thereof.

So, I asked him, “Why don’t you just buy him a new car?”

“Excuse me,” he asked indignantly?

“Well, if you are willing to pay $20,000 more per year for the next 10 years just to help him out, it seems to me that you can buy him a new car for a lot less than $200,000 and you’ll both be better off!”

Click.

“Hello,” I asked? But it was too late, he apparently didn’t appreciate my direct manner of offering advice.

Sometimes truth, like market downturns, isn’t pleasant. But the lesson of controlling the controllable is one that I continue to apply each day. In addition to building portfolios with low cost funds and waiving our advisory fees when the market drops, we have been harvesting tax losses in taxable accounts, and using dividend, interest, and capital gain distributions to allocate to depressed portions of our clients’ portfolios.

None of that guarantees we’ll do better than a relative with a new job, or a salesperson claiming some prescient ability to foretell the future, but I like our chances. Get in touch if you want to discuss yours’.