Have you heard the saying about the difference between life and school? In life, we frequently take the test before learning the lesson. The upside is that often that knowledge we come by honestly is the most enduring, except perhaps in the world of investing. Sounds crazy? Well, you know what they say about repeating the same thing and expecting a different result? Here are a couple of answers to the next test to help you be more successful.

Lesson 1: Don’t Chase Performance

Leading the list of investor mistakes is succumbing to the allure of chasing past performance. It is no coincidence that regulators require investment companies to offer a disclaimer that “past performance is no guarantee of future results”, or something similar whenever they talk about results.

There may be no better example of that in the past few years than the ARK Innovation ETF (ARKK), managed by Cathie Wood. If you have tuned into CNBC or other financial press in the last several years, you have almost certainly seen either ARKK or Ms. Wood highlighted. That is largely because for the five-year period from January 1, 2017 to December 31, 2021, her fund returned 409.3% versus the S&P 500’s return of 112.89%.

Investors certainly noticed. In 2019 alone, about $15 billion of new assets flowed into the fund.

Had you observed that remarkable performance and invested $100,000 in ARKK on January 1, 2022, you would have incurred an approximate $63,000 loss by October 31, 2023. Although the S&P 500 experienced a decline during the same time frame, it would have incurred losses of approximately $12,000.

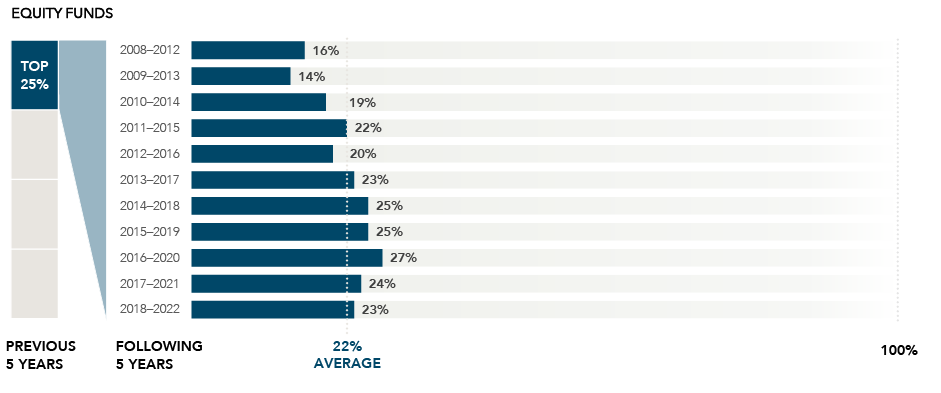

A look at performance data across the industry for the past 20 years suggests that ARKK isn’t all that unique. In fact, only about 22% of the funds in the top quartile of five-year performance remained in the top quartile of performance over the following five years. See Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1. Percentage of US-domiciled equity funds that were top-quartile performers in consecutive 5-year periods

Source: Dimensional 2023 Funds Landscape

We are hardwired by evolution to recognize patterns to survive. Recognizing the patterns of predator movements, seasonal changes, or locations of food sources enabled our ancestors to anticipate risks and opportunities. Over time, the ability to quickly recognize and respond to patterns became an evolutionary advantage.

This advantage, however, can lead to problems for investors who see patterns where there is just random chance and luck playing out. Psychologists call the tendency to see patterns in nebulous stimuli "pareidolia". It may be perfectly normal and harmless if that results in you seeing faces in the clouds, but when it comes to investing, confusing randomness with order can be very expensive.

A study by Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman titled “Judgement under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases” demonstrated that people tend to take mental shortcuts. Before their 1975 paper, in 1971, Tversky and Kahneman conducted an experiment where participants were shown a sequence of "random" coin tosses that had been pre-arranged. The sequence contained certain patterns, such as a run of consecutive heads. Participants were then asked to predict the next outcome.

Those who were correct with their initial guesses began to consider themselves to be better than average at predicting the toss of a coin. More surprisingly, 40% of them also believed that they could improve their “skill” with additional practice.

Investors are prone to deriving similar misplaced confidence by relying on past performance to pick tomorrow’s winners.

Lesson 2: Don’t Overreact to Market Events

Loss aversion is a psychological concept which refers to how the emotional lows of investment losses are felt harder and last longer than the highs of comparable-sized gains. This leads us to focus on short-term price gyrations, particularly during periods of market upheaval.

The problem is that these “risk reductions” are often very costly in the long term. Data shows investors who overreact to market events typically end up doing worse than if they stuck to their long-term plan.

For example, in the past 20 years, the Russell 3000’s steepest declines during the year averaged 15%, ranging from -3% in 2017 to -49% in 2008. In 17 of those 20 years, US stocks ended up with gains for the year. As you can see in Exhibit 2, investors that sought shelter after a loss would have missed out on gains more often than not.

Exhibit 2. YEAR-BY-YEAR RETURNS, WITH STEEPEST DECLINE WITHIN EACH YEAR

Russell 3000 Index, January 2003–December 2022

Source: Frank Russell Company. They are also the source and owner of the trademarks, service marks, and copyrights related to the Russell Indexes. Data is calculated off rounded daily returns. US market is represented by the Russell 3000 Index. Largest intra-year decline refers to the largest market decrease from peak to trough during the year.

Exhibit 3 illustrates the significant effects that can result from even a brief period of time spent out of the market. The evidence suggests we should stay put through good times and bad because there is no proven way to time the market. Even a brief window of high returns missed can have a significant effect on overall performance. Staying the course may not sound very sophisticated, but it guarantees that you're in a position to take advantage of what the market has to offer.

Exhibit 3. Missed Opportunity

Russell 3000 Index total return, 1998-2022

Source: Frank Russell Company

Our cognitive biases, along with our natural predispositions, can frequently mislead us when it comes to investing. Our deep-rooted psychological tendencies to run from impending danger and the pull of recent accomplishments show up in our investing decisions, frequently to our harm. It's important to be aware of these tendencies, but it's much more important to deliberately act against them. Recall that in the world of finance, past success does not guarantee future results, and our judgment can be influenced by our emotions.

If you’re not sure if you are prepared for the next test life has in store, get in touch, we probably already have some answers.

Past performance, including hypothetical performance, is not a guarantee of future results.