Trivia time: how many stocks make up the Wilshire 5000

Total Market Index (a widely used benchmark for the US equity market)?

While the logical guess might be 5,000, as of December 31, 2016, the index actually contained around 3,600 names. In fact, the last time this index contained 5,000 or more companies was at the end of 2005.[1] This mirrors the overall trend in the US stock market. In the past two decades there has been a decline in the number of US-listed, publicly traded companies. Should investors in public markets be worried about this change? Does this mean there is a material risk of being unable to achieve an adequate level of diversification for stock investors? We believe the answer to both is no. When viewed through a global lens, a different story begins to emerge—one with important implications for how to structure a well-diversified investment portfolio.

U.S. AGAINST THE WORLD

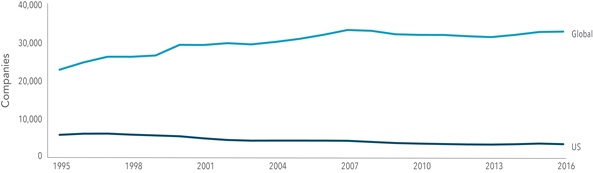

When looked at globally, the number of publicly listed companies has not declined. In fact, the number of firms listed on US, non-US developed, and emerging markets exchanges has increased from about 23,000 in 1995 to 33,000 at the end of 2016. (See Exhibit 1.)

It should be noted, however, that this number is substantially larger than what many investors consider to be an investable universe of stocks. For example, one well-known global benchmark, the MSCI All Country World Index Investable Market Index (MSCI ACWI IMI) contains between 8,000 and 9,000 stocks. This index applies restrictions for inclusion such as minimum market capitalization, volume, and price. For comparison, the Dimensional investable universe, at around 13,000 stocks, is broader than the MSCI ACWI IMI.

Exhibit 1. Number of Publicly Listed Companies

Source: Bloomberg

While it is true that in the US there are fewer publicly listed firms today than there were in the mid-1990s (a decrease of about 2,500), it is clear that the increase in listings both in developed markets outside the US and in emerging markets has more than offset the decline in US listings. Although there is no consensus about why US listings have decreased over this period of time, a number of academic studies have explored possible reasons for this change. One line of investigation considered if changes in the regulatory environment for listed companies in the US relative to other countries may explain why there are fewer listed firms. Another considered if, since the 2000s, private companies have had a greater propensity to sell themselves to larger companies rather than list themselves. In either case, the implication for investors based on the numbers alone is clear—the number of publicly listed companies around the world has increased, not decreased.

A GLOBAL APPROACH

In the US, with thousands of stocks available for investment today, it is unlikely that this change will meaningfully impact an investor’s ability to efficiently pursue equity market returns in broadly diversified portfolios. It is also important to note that a significant fraction of the publicly available global market cap remains listed on US exchanges. As noted in Exhibit 2, the weight of the US in the global market is approximately 50–55%. For comparison, it was approximately 40% in 1995.

For investors looking to build diversified portfolios, the implications of the trend in listings are also clear. The global equity market is large and represents a world of investment opportunities, nearly half of which are outside of the US. While diversifying globally implies an investor’s portfolio is unlikely to be the best performing relative to any one domestic stock market, it also means it is unlikely to be the worst performing. Diversification provides the means to achieve a more consistent outcome and can help reduce the risks associated with overconcentration in any one country. By having a truly global investment approach, investors have the opportunity to capture returns wherever they occur.

Exhibit 2. Percent of World Market Capitalizations as of December 31, 2016

Data provided by Bloomberg. Market cap data is free-float adjusted and meets minimum liquidity and listing requirements. Many nations not displayed. Totals may not equal 100% due to rounding. China market capitalization excludes A-shares, which are generally only available to mainland China investors.

CONCLUSION

While there has been a decline in the number of US-listed, publicly traded companies, this decline has been more than offset by an increase in listings in non-US markets. While the reasons behind this trend are not clear, the implications for investors today are clearer—to build a well-diversified portfolio, an investor has to look beyond any single country’s stock market and take a global approach.

[1]. Source: Wilshire Associates.

Source: Dimensional Fund Advisors LP.

Past performance is no guarantee of future results. There is no guarantee an investing strategy will be successful. Diversification does not eliminate the risk of market loss. Investing risks include loss of principal and fluctuating value. International investing involves special risks such as currency fluctuation and political instability. Investing in emerging markets may accentuate these risks.

All expressions of opinion are subject to change. This article is distributed for informational purposes, and it is not to be construed as an offer, solicitation, recommendation, or endorsement of any particular security, products, or services.

Indices, such as the MSCI All Country World Index Investable Market Index (MSCI ACWI IMI) are not available for direct investment.

[1]. Source: Wilshire Associates.